Now that he’s been convicted of criminal contempt of Congress and may (again) be facing jail time, the repulsive Steve Bannon is back in the news.

Of all the orcs who dance attendance on their bloated master,

Bannon may be the most physically disgusting. With his greasy, shaggy hair, bloodshot,

baggy eyes, porcine jowls, pocked and raddled hide which alternately flushes

and pales in a manner indicative of significant cardiac issues, and a physique

of about the same shape and consistency as a rotten watermelon, you just can’t

help but wonder if the evil in his soul hasn’t corrupted the rest of him. It’s

not often that I agree with #FatDonnyPeaches, but when he called Bannon “Sloppy

Steve” during one of their little tiffs, I found myself hard-pressed to

contradict him.

|

| Does this make any sense to you? Keep reading. It will. |

Considering what all those layers must do on a hot day to a guy with a sagging, flabby build and, if appearance is anything to go by, questionable personal hygiene, such a getup understandably mystifies people.

“Steve

Bannon’s Penchant for Wearing Several Shirts at Once Confuses People Across the

Political Spectrum,” reads a 2022 headline from Distractify.

“Why does

Steve Bannon wear all his shirts at once?” wonders Morwenna Ferrier in The

Guardian, quoting Joshua Green, Bannon’s biographer, who says, “I’ve never been

able to figure it out. I don’t have any idea. It’s the weirdest sartorial style I

have ever encountered.”

Karen Fratti at Hello Giggles indulges in a little journalistic

bait and switch with the teasing headline “We finally

know why Steve Bannon always wears so many shirts,” but

then fails to deliver, when she concludes, “So we don’t really know precisely

why Bannon wears multiple shirts… America may never know.”

Even the venerable GQ, which really ought to know better, fumbled

the ball in a piece entitled, “Steve

Bannon Doesn’t Understand Layering,” the tone of which hovered somewhere

between bewildered and condemnatory.

Olivia Nuzzi at The Cut gets a little closer with her article “Here’s Why

Steve Bannon Wears So Many Shirts” wherein she quotes friends of his

who claim that he picked up the habit at Benedictine College Preparatory, the

Catholic military institute he attended as a teenager. But, as someone who went there pointed out, students wear the kind of army-guy cosplay

uniforms that such schools require (and those don’t come with multiple shirts),

and added, “I don’t know what the uniform was exactly when Mr. Bannon was

here,” but “there’s not multiple shirts.”

But we’re getting there, and the answer is far more interesting than it may

seem at first glance. What began as a “What the actual fuck, Hog Steve? Forget

to take off yesterday’s clothes before you put today’s on?” gives way to a

question that that sheds significant light on the mind of Steve Bannon. Which,

considering he got us into the mess we’re in now, is an important question.

The semiotics of clothing is a woefully underutilized analytic tool, and I

don’t understand why pundits and commentators don’t use it more. What people

wear tells you an awful lot about them. Frequently more than they’d like

you to know. They tell us not only about a person’s background, but what the

wearer WANTS us to think about his background.

§§§

I read these articles with a chuckle because I knew immediately what he was up to, as would

anyone who, like me,

1) Grew up in the 80’s, and

2) Went to a college where the pretensions of its students far outweighed the school’s actual prestige.

This last is a crucial piece of the puzzle, and bears a little

explication.

I went to a small, private, liberal arts Christian college in

Indiana called Taylor University. This was, out of a strong field of

contenders, the biggest mistake I ever made, but that’s a topic for another

blog post.

As a Christian college, Taylor by definition lacked the prestige

of secular schools of similar size and vintage (1846) like a Bates (1855), an Amherst (1821) or a

Swarthmore (1864). It didn’t even have the prestige of a Midwestern liberal arts

college like a DePauw or a Denison.

Nonetheless, it had a bit of cachet in the evangelical world, and had among its students a certain group of kids—largely from the east coast, but with a smattering from places like Cleveland, Chicago and Detroit—from wealthy families high up in the food chain of the Christian world. These kids all seemed to know each other from having gone to the same Christian prep schools and Christian summer camps. Many of their parents sat on the boards of the same Christian institutions.

At Taylor, they formed an elite clique which attracted second-tier hangers-on (like me): kids whose families

were not part of this wealthy Christian network, but who were mesmerized by their tales of boarding school, summers spent sailing on the Atlantic and visiting each other's summer houses, and their general aura of privilege, superiority and connectedness.

There was another reason I gravitated toward them: I knew Taylor was no great

shakes. It chewed at me. But hanging around these kids let me pretend Taylor

was a lot more prestigious than it was (part of the “Ivy League of Christian schools,”

as another hanger-on like me called it). I aped their attitudes, their mannerisms and their look, which, for lack of a better word, we’ll call “preppy.”

I had no idea what I was doing. My background was nothing like

theirs (St. Louis Jewish on my mother’s side, Indiana farmers on my father's).

Like any tyro, I made a mortifying hash of it, and suffered my share of deserved ridicule. I needed an instruction

manual. Luckily, I found one at the public library. It was Lisa Birnbach’s “The

Official Preppy Handbook.”

The Handbook had been out for about nine years by the time I found

it and it was, ostensibly, a work of satire mocking the foibles and

lifestyles of America’s old-money elites. But the book’s almost sociological

precision tells a different story. Birnbach might claim to mock her subject, but

it’s pretty obvious that she wanted to be part of it, and so did I.

We weren’t alone. The book’s impact in the 80’s was enormous. It exposed, in anthropological

detail, a world that most middle-class Americans had vaguely intimated from

having seen the Kennedys or having read “A Separate Peace” or “Love Story”, but

never really known anything about. The Handbook revealed a world

of inherited wealth and prestige, privilege, and luxury. In a money-obsessed

decade, it wasn’t satirical, it was aspirational. Those who read it wanted to be a part of it. God knows I did.

Well, tough luck. Pedigree is fundamental to prepdom, and you

can’t fake that. You’re either born to a long line of loaded blueblooded

Episcopalians with tons of cash or you aren’t. But there WAS a consolation

prize: the Handbook showed you could dress like it.

And doing so was easier and cheaper than you might have thought.

One of the defining characteristics of this class is its abhorrence of

ostentation, which means the clothes really aren’t all that expensive. They’re

good quality, but brands like Orvis, Pendleton, Gant, L.L. Bean, J. Press, and

Brooks Brothers—and plagiarists like Lands End, Ralph Lauren, J. Crew and

Vineyard Vines—won’t break the bank.

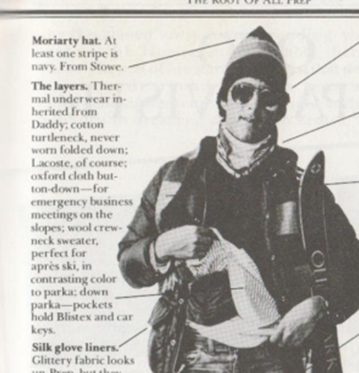

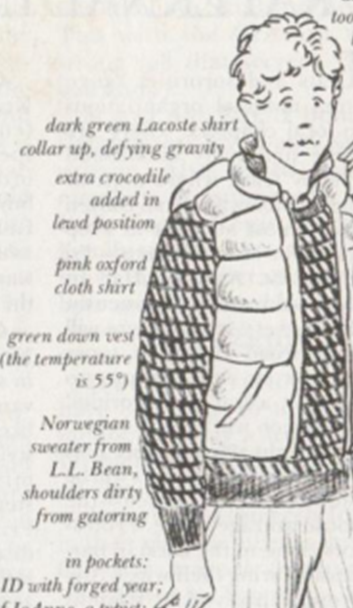

Anyone who pored over the Handbook would instantaneously know where

Bannon’s shirt over shirt over shirt look came from:

This is what Bannon's up to--appropriating the look so that people think he's the old-money, elite, Establishment.

But he doesn’t quite pull it off. He fails (spectacularly) in two ways:

1. He doesn’t get the attitude.

After years of mulling this over, I think I’ve figured out what the real key to dressing like a genuine prep is. It’s not the careful assemblage of elements. It’s insouciance.

"Trying too hard" is the antithesis of the prep ethos. Real preps just don’t give a

fuck about projecting an image. They don’t need to. They have nothing

to prove. There’s no

intentionality. They simply wake up from a hangover in their dorm room at

Dartmouth or Brown or Vanderbilt or wherever with five minutes to get to class

and they throw on whatever’s near to hand. If it’s cold, they’ll throw on a couple

of shirts, maybe a jacket that they found wadded up under the bed and they’ll

dash out rumpled, unmatched, uncombed and untucked.

And they’ll look fabulous doing it. Because it’s not really about

what you wear, it’s how you wear it. If you wear it with confidence, then

you’ll look terrific in whatever you’ve got on.

As the great menswear writer G. Bruce Boyer said of George H.W.

Bush, who was the real McCoy (Greenwich Country Day, Phillips Academy, Yale), “He has that Old Money Look and will wear

boat shoes and checks with plaids in that kind of nonchalant way that says

“screw you.”

And as Boyer said of someone who doesn’t

pull it off (Tucker Carlson), “I look at him and say it may be natural for him,

but it doesn’t look natural. It looks like he’s trying too hard, but I

can’t quite put my finger on why.”

In other words, even with all the

right ingredients, if you don’t have the right attitude, it’ll show.

2. 2. He doesn’t know when to do it.

Real preps know when to grow up. By the time they reach adulthood, they know damn well not to dress from the dorm room floor. They, like the rest of us, put on suits and ties and go to work, leaving the shirt over shirt (over shirt over shirt) look back at college. Look at the real preps: William Barr (Horace Mann, Columbia, George Washington Law School) and John Bolton (McDonogh School, Yale, Yale Law).

Barring certain unprep elements of

their backgrounds (Barr’s father was Jewish and Bolton’s was a fireman), they

both have pretty unimpeachable prep credentials, and it shows in how they

dress. Unless you’re looking, you’d never notice (which is precisely what real preps want), but there are subtle, yet undeniable tells: the roll of the collar, the width and

knot of tie and lapels, the tie patterns (repp or small repeating images),

the cut of the suit, the shape of the shoe’s toe.

Unlike the rest of the Trump coterie, they never

started dressing like #FatDonnyPeaches. Look at how Kevin McCarthy's and Mike Pence's outfits changed over the four miserable years of his regime. But Barr and Bolton stuck to the same

rumpled Brooks Brothers button-downs, boxy J. Press suits, and round horn- or

wire-rimmed glasses they’ve worn since the 80’s.

(Such sartorial independence

indicates a certain independence of mind. Barr and Bolton’s loyalties were

never to #FatDonnyPeaches himself, but rather to their convictions. They’re

ghastly convictions, but at least they have them. This is borne out by their

conduct. Bolton left in disgust and wrote a tell-all book, and Barr, in the

absence of any evidence of “widespread voter fraud,” informed his boss that DOJ

wasn’t going to pursue the matter and quit.)

In essence, they echo the lie he sold to half the nation—that a cheap and tacky real estate developer was a true titan of industry, that a thrice-divorced perpetual adulterer was a paragon of Christian morality, and that a known crook was the proper repository of the nation’s trust.

If only we’d known what all those shirts meant.