I Love Mechanical Pencils

Occasional musings from someone who's a jerk in print or on the screen, but generally pretty well-behaved in person. Generally.

Tuesday, November 12, 2024

Post Mortem

Friday, August 12, 2022

Of Sloppy Steve and Sartorial Semiotics

Now that he’s been convicted of criminal contempt of Congress and may (again) be facing jail time, the repulsive Steve Bannon is back in the news.

Of all the orcs who dance attendance on their bloated master,

Bannon may be the most physically disgusting. With his greasy, shaggy hair, bloodshot,

baggy eyes, porcine jowls, pocked and raddled hide which alternately flushes

and pales in a manner indicative of significant cardiac issues, and a physique

of about the same shape and consistency as a rotten watermelon, you just can’t

help but wonder if the evil in his soul hasn’t corrupted the rest of him. It’s

not often that I agree with #FatDonnyPeaches, but when he called Bannon “Sloppy

Steve” during one of their little tiffs, I found myself hard-pressed to

contradict him.

|

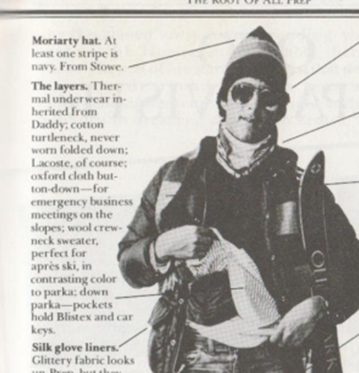

| Does this make any sense to you? Keep reading. It will. |

Considering what all those layers must do on a hot day to a guy with a sagging, flabby build and, if appearance is anything to go by, questionable personal hygiene, such a getup understandably mystifies people.

“Steve

Bannon’s Penchant for Wearing Several Shirts at Once Confuses People Across the

Political Spectrum,” reads a 2022 headline from Distractify.

“Why does

Steve Bannon wear all his shirts at once?” wonders Morwenna Ferrier in The

Guardian, quoting Joshua Green, Bannon’s biographer, who says, “I’ve never been

able to figure it out. I don’t have any idea. It’s the weirdest sartorial style I

have ever encountered.”

Karen Fratti at Hello Giggles indulges in a little journalistic

bait and switch with the teasing headline “We finally

know why Steve Bannon always wears so many shirts,” but

then fails to deliver, when she concludes, “So we don’t really know precisely

why Bannon wears multiple shirts… America may never know.”

Even the venerable GQ, which really ought to know better, fumbled

the ball in a piece entitled, “Steve

Bannon Doesn’t Understand Layering,” the tone of which hovered somewhere

between bewildered and condemnatory.

Olivia Nuzzi at The Cut gets a little closer with her article “Here’s Why

Steve Bannon Wears So Many Shirts” wherein she quotes friends of his

who claim that he picked up the habit at Benedictine College Preparatory, the

Catholic military institute he attended as a teenager. But, as someone who went there pointed out, students wear the kind of army-guy cosplay

uniforms that such schools require (and those don’t come with multiple shirts),

and added, “I don’t know what the uniform was exactly when Mr. Bannon was

here,” but “there’s not multiple shirts.”

But we’re getting there, and the answer is far more interesting than it may

seem at first glance. What began as a “What the actual fuck, Hog Steve? Forget

to take off yesterday’s clothes before you put today’s on?” gives way to a

question that that sheds significant light on the mind of Steve Bannon. Which,

considering he got us into the mess we’re in now, is an important question.

The semiotics of clothing is a woefully underutilized analytic tool, and I

don’t understand why pundits and commentators don’t use it more. What people

wear tells you an awful lot about them. Frequently more than they’d like

you to know. They tell us not only about a person’s background, but what the

wearer WANTS us to think about his background.

§§§

I read these articles with a chuckle because I knew immediately what he was up to, as would

anyone who, like me,

1) Grew up in the 80’s, and

2) Went to a college where the pretensions of its students far outweighed the school’s actual prestige.

This last is a crucial piece of the puzzle, and bears a little

explication.

I went to a small, private, liberal arts Christian college in

Indiana called Taylor University. This was, out of a strong field of

contenders, the biggest mistake I ever made, but that’s a topic for another

blog post.

As a Christian college, Taylor by definition lacked the prestige

of secular schools of similar size and vintage (1846) like a Bates (1855), an Amherst (1821) or a

Swarthmore (1864). It didn’t even have the prestige of a Midwestern liberal arts

college like a DePauw or a Denison.

Nonetheless, it had a bit of cachet in the evangelical world, and had among its students a certain group of kids—largely from the east coast, but with a smattering from places like Cleveland, Chicago and Detroit—from wealthy families high up in the food chain of the Christian world. These kids all seemed to know each other from having gone to the same Christian prep schools and Christian summer camps. Many of their parents sat on the boards of the same Christian institutions.

At Taylor, they formed an elite clique which attracted second-tier hangers-on (like me): kids whose families

were not part of this wealthy Christian network, but who were mesmerized by their tales of boarding school, summers spent sailing on the Atlantic and visiting each other's summer houses, and their general aura of privilege, superiority and connectedness.

There was another reason I gravitated toward them: I knew Taylor was no great

shakes. It chewed at me. But hanging around these kids let me pretend Taylor

was a lot more prestigious than it was (part of the “Ivy League of Christian schools,”

as another hanger-on like me called it). I aped their attitudes, their mannerisms and their look, which, for lack of a better word, we’ll call “preppy.”

I had no idea what I was doing. My background was nothing like

theirs (St. Louis Jewish on my mother’s side, Indiana farmers on my father's).

Like any tyro, I made a mortifying hash of it, and suffered my share of deserved ridicule. I needed an instruction

manual. Luckily, I found one at the public library. It was Lisa Birnbach’s “The

Official Preppy Handbook.”

The Handbook had been out for about nine years by the time I found

it and it was, ostensibly, a work of satire mocking the foibles and

lifestyles of America’s old-money elites. But the book’s almost sociological

precision tells a different story. Birnbach might claim to mock her subject, but

it’s pretty obvious that she wanted to be part of it, and so did I.

We weren’t alone. The book’s impact in the 80’s was enormous. It exposed, in anthropological

detail, a world that most middle-class Americans had vaguely intimated from

having seen the Kennedys or having read “A Separate Peace” or “Love Story”, but

never really known anything about. The Handbook revealed a world

of inherited wealth and prestige, privilege, and luxury. In a money-obsessed

decade, it wasn’t satirical, it was aspirational. Those who read it wanted to be a part of it. God knows I did.

Well, tough luck. Pedigree is fundamental to prepdom, and you

can’t fake that. You’re either born to a long line of loaded blueblooded

Episcopalians with tons of cash or you aren’t. But there WAS a consolation

prize: the Handbook showed you could dress like it.

And doing so was easier and cheaper than you might have thought.

One of the defining characteristics of this class is its abhorrence of

ostentation, which means the clothes really aren’t all that expensive. They’re

good quality, but brands like Orvis, Pendleton, Gant, L.L. Bean, J. Press, and

Brooks Brothers—and plagiarists like Lands End, Ralph Lauren, J. Crew and

Vineyard Vines—won’t break the bank.

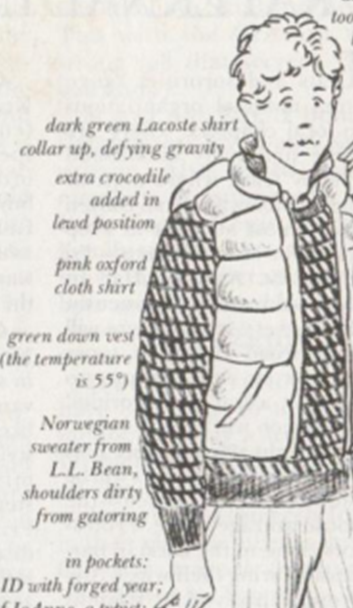

Anyone who pored over the Handbook would instantaneously know where

Bannon’s shirt over shirt over shirt look came from:

This is what Bannon's up to--appropriating the look so that people think he's the old-money, elite, Establishment.

But he doesn’t quite pull it off. He fails (spectacularly) in two ways:

1. He doesn’t get the attitude.

After years of mulling this over, I think I’ve figured out what the real key to dressing like a genuine prep is. It’s not the careful assemblage of elements. It’s insouciance.

"Trying too hard" is the antithesis of the prep ethos. Real preps just don’t give a

fuck about projecting an image. They don’t need to. They have nothing

to prove. There’s no

intentionality. They simply wake up from a hangover in their dorm room at

Dartmouth or Brown or Vanderbilt or wherever with five minutes to get to class

and they throw on whatever’s near to hand. If it’s cold, they’ll throw on a couple

of shirts, maybe a jacket that they found wadded up under the bed and they’ll

dash out rumpled, unmatched, uncombed and untucked.

And they’ll look fabulous doing it. Because it’s not really about

what you wear, it’s how you wear it. If you wear it with confidence, then

you’ll look terrific in whatever you’ve got on.

As the great menswear writer G. Bruce Boyer said of George H.W.

Bush, who was the real McCoy (Greenwich Country Day, Phillips Academy, Yale), “He has that Old Money Look and will wear

boat shoes and checks with plaids in that kind of nonchalant way that says

“screw you.”

And as Boyer said of someone who doesn’t

pull it off (Tucker Carlson), “I look at him and say it may be natural for him,

but it doesn’t look natural. It looks like he’s trying too hard, but I

can’t quite put my finger on why.”

In other words, even with all the

right ingredients, if you don’t have the right attitude, it’ll show.

2. 2. He doesn’t know when to do it.

Real preps know when to grow up. By the time they reach adulthood, they know damn well not to dress from the dorm room floor. They, like the rest of us, put on suits and ties and go to work, leaving the shirt over shirt (over shirt over shirt) look back at college. Look at the real preps: William Barr (Horace Mann, Columbia, George Washington Law School) and John Bolton (McDonogh School, Yale, Yale Law).

Barring certain unprep elements of

their backgrounds (Barr’s father was Jewish and Bolton’s was a fireman), they

both have pretty unimpeachable prep credentials, and it shows in how they

dress. Unless you’re looking, you’d never notice (which is precisely what real preps want), but there are subtle, yet undeniable tells: the roll of the collar, the width and

knot of tie and lapels, the tie patterns (repp or small repeating images),

the cut of the suit, the shape of the shoe’s toe.

Unlike the rest of the Trump coterie, they never

started dressing like #FatDonnyPeaches. Look at how Kevin McCarthy's and Mike Pence's outfits changed over the four miserable years of his regime. But Barr and Bolton stuck to the same

rumpled Brooks Brothers button-downs, boxy J. Press suits, and round horn- or

wire-rimmed glasses they’ve worn since the 80’s.

(Such sartorial independence

indicates a certain independence of mind. Barr and Bolton’s loyalties were

never to #FatDonnyPeaches himself, but rather to their convictions. They’re

ghastly convictions, but at least they have them. This is borne out by their

conduct. Bolton left in disgust and wrote a tell-all book, and Barr, in the

absence of any evidence of “widespread voter fraud,” informed his boss that DOJ

wasn’t going to pursue the matter and quit.)

In essence, they echo the lie he sold to half the nation—that a cheap and tacky real estate developer was a true titan of industry, that a thrice-divorced perpetual adulterer was a paragon of Christian morality, and that a known crook was the proper repository of the nation’s trust.

If only we’d known what all those shirts meant.

Tuesday, March 1, 2022

A Modest Proposal for a Thought Experiment.

I know this is long, but bear with me.

The year is 2035, and the United States is on the ropes like it's never been before. A long economic decline and deep internal rifts have weakened the country from inside, and it's flat broke after a two-decade Cold War with the Pacific Security Alliance, an organization of states in east Asia led by China.

The PSA's overwhelming military might, fueled by a juggernaut economy, is one that the U.S. simply can't compete with. We try. But eventually and inevitably, we realize that we're outgunned.

Finally, the U.S. accepts the inevitable. We can't maintain our hegemony even over our own sphere of influence. We disband the OAS, the Organization of American States, and we admit that our time as a global superpower is kaput.

We're a little worried, however, about Korea. As we contract, we can no longer maintain the South Korean client state. North Korea, still led by Kim Jong Un and backed by China's military and economic might, is pushing hard for reunification.

As a condition of Korean reunification, the United States and China hammer out a deal. We'll leave, but China agrees not to extend the PSA, into our traditional sphere of influence, and the U.S. leaves East Asia, likely for good.

A coup is launched in Washington. The president is deposed, and a China-friendly president assumes power. He's a coarse, uneducated opiate addict from the sticks who embarrasses the United States, but who is lauded internationally as a champion of democracy and the man who will lead America out of its dark past and into the new international order.

The collapse of the United States is devastating internally. What's left of our economy implodes, our standard of living plummets, and the United States, the existence of which seemed all but eternally assured, comes apart. Texas and California, which between them constitute the sixth largest economy in the world, spin off. and declare their independence.

Losing two huge chunks of the country is traumatic and a colossal blow to our national ego, but it's survivable. With strong linguistic, cultural and economic ties to the United States, they appear to remain, for now, within the United States' faded and shrunken orbit.

With a compliant puppet as head of state, the looting of the United States begins. There's some pro forma concern about America's still formidable nuclear arsenal, and some proposals floated to remove our warheads from our territory by force, but nothing really comes of them. The world is too busy ripping America off. Foreign venture capitalists, largely from Asia, working in tandem with a crop of shady American billionaires who have emerged from the rubble to rob their own country, buy up American farmland, American industry, American railroads, airlines and airports, mines, oilfields, refineries, refineries, truck fleets and pipelines. America's vast natural resources are systematically despoiled by international capitalists who take whatever they feel like with impunity.

The American economy continues to plunge. Overnight, people's 401ks disappear, and their savings dry up like vapor. There's mass starvation. Desperate women turn to prostitution in astounding numbers. American prostitutes become so ubiquitous in the brothels of Montreal, Havana, Kingstown and Mexico City that a new slang term for whore emerges: "Kellys." For many families, the income that the Kellys send home is their only source of revenue.

Less than five years after the PSA assured the United States that it would stay out of America's traditional sphere of influence, they renege. Mexico, Guatemala, Nicaragua and Canada all join the PSA to great fanfare. The United States is powerless to resist.

The American president, his body gross and corrupted by indulgence and smack, croaks. A new president takes his place. The world isn't sure what to make of him. He's a career CIA man, and sizable chapters of his pre-political life remain opaque. What is known of him is that he is an American patriot and he regards the collapse of the United States and its hegemony over the Western Hemisphere as, quote, "one of the greatest geopolitical disasters ever to befall humanity."

The new president immediately goes to work. He attacks the opioid epidemic by cutting off supply and lining up opioid dealers and shooting them. The world press (without noting that much of these opiates come from China) decries his dismissal of due process.

Not a believer himself, he makes an alliance with the churches, viewing them as potential allies and forces for morality and stability. Such open support for religion, after decades of derision from the cultural elite, comes as both a surprise and a comfort to the American people.

He begins rebuilding American armed forces. The international commentariat mutters darkly about "the Eagle sharpening its claws again," and Beijing begins to pay close attention.

Meanwhile, Mexican-American separatists in Arizona and New Mexico see America's weakness as opportunity to secede and rejoin themselves to Mexico. To show they mean business, they blow up some movie theatres and government buildings in Chicago, Detroit and Nevada. A bloody guerrilla war ensues.

The new American president grinds them down and stamps out the insurrection. It's brutal, but it works. He is excoriated in the international press as a monster, a human-rights violator on a grand scale, and bloodthirsty tyrant. Arguably, he is. But he's got a country to pacify, and public opinion, particularly after the Mexican-American attacks on civilian targets, won't be satisfied with anything less than complete victory.

The Mexican-American insurrection dealt with, the new president then goes to town on ending the rape of the country. Using anti-corruption as a platform, he arrests those American billionaires who aren't getting on board with his program. The more problematic ones he imprisons. He replaces them with his own long-time associates, people whose loyalty he can trust. He ends the wholesale looting of the country, and he nationalizes the megacompany "joint ventures", rerouting the revenue into the national coffers.

There's a lot of pearl-clutching from the international commentariat about "the stifling of free enterprise." The international papers call him:

- A domestic tyrant

- A murderer (because, truth be told, he has bumped off a number of his enemies both at home and abroad)

- Contemptuous of institutions (or at least the ones he's not a member of)

- A deliberate saboteur of the world order, gleefully throwing a monkey-wrench into the smoothly running Pax Sinaicana

But he's attracted negative attention. The U.S., say policymakers in Beijing, Seoul and Singapore, must not now and never in future be allowed to become a danger to world order again.

The PSA immediately sponsors a coup in Texas, forcing the U.S.-aligned president of Texas into exile ad replacing him with one more sympathetic to the PSA and the Chinese-led world economic order. They begin selling their produce, their oil and their beef not to the U.S., but to the partner states of the PSA.

The U.S. president isn't happy about that. He views it as a hostile act, as, in fact, it is. But there isn't much he can do about it.

What he can, and does do, is support those Texans who still consider themselves Americans they're concentrated in the panhandle). He supplies them with arms, money, and other material support in their ongoing low-boil insurrections against the Chinese-aligned government in Austin.

Things become a little more serious, however, when Texas begins making noises about repossessing Sheppard AFB in north Texas, along the Oklahoma border. For a long time, this base hasn't been a problem. Texas lets the U.S. use it in the interest of good relations. But the change in direction and the U.S.'s possible loss of it reconfigure the calculus significantly. This base is critical to the U.S.'s security. In desperation, the U.S. scrambles the personnel already there, and occupies the area along the Red River where the base is located. It's not tough to do--most of the people living there are U.S.-aligned anyhow, and glad to be back in the Union.

But it's regarded internationally as an act of lawlessness, an attack on a sovereign nation. Dark comparisons to Hitler and the Indian Wars are made.

The PSA kicks into high gear. At a summit in Tokyo (which is now part of the PSA), China announces that both California and Texas will become fully-fledged members of the PSA. Vietnam and Japan, both of which have tussled with the U.S. before, express some hesitation. It's also noted that Texas, as a sinkhole of corruption, may not meet the standards of transparency necessary for membership in the PSA, but their voices are dismissed. It's China who calls the shots, and China wants Texas and California in the PSA.

This is unacceptable to the American president. California and Texas are his country's largest trading-partners. Traditionally, they've always been part of the United States. And strategically, it could be disastrous. The panhandle cuts deep into the U.S. heartland, uncomfortably close to the national breadbasket of Kansas and to major U.S. military installations in New Mexico. Having a Chinese ally deep in the interior of your landmass is a dagger at your heart.

He objects strongly. He says, openly and publicly, that PSA membership for Texas is unacceptable. He points out, reasonably enough, that the PSA is already on his northern and southern borders--both Canada and Mexico are members. He says that the United States has no interest in either annexing Texas, nor any plans to threaten its independence, but, at the very most, he needs to keep Texas officially neutral.

(Privately, he'd like Texas back. But he knows he has no chance of that. Half the country likes its independence, and he has no desire to get bogged down in a war of occupation. So his demands remain well within the realm of both the possible, and, from his point of view, the reasonable.)

It's a bitter pill to swallow, having to settle for the neutrality of an area that used to be part of your country. But it's the most he can ask for and expect to get. Still, it doesn't work.

"The U.S. is on the march again," the world press shrieks. "The American president, a sinister tyrant at home, is once again threatening the peace and stability of the region. It's nothing but old-fashioned American Manifest Destiny raising its ugly head again. And after Texas, then what? Is he going to take back California, too? And then Mexico? And then the rest of Central America? The Eagle can never be satisfied. His appetite for conquest and bloodshed knows no bounds. He's an international rebel and he MUST BE STOPPED NOW."

The president, with no other choice, begins massing American troops on the borders of Oklahoma and Louisiana. The Texas president, gambling on support from China and the PSA member states in the Western hemisphere, remains defiant. The international press shrieks loudly about Texas's right to national self-determination. They point to Texas's long history of resistance to oppression from Washington, like the late Governor Abbott's historic resistance against federal mask-mandates during the COVID-19 outbreak. And then someone dusts off Texas's ancient history.

"Did you know," the articles crow, "that Texas actually began as an independent Republic? That in 1835, Texas revolted against Mexico and declared itself the Republic of Texas in 1836? That the heroic Mirabeau Lamar advocated permanent independence, but the nefarious U.S. agent Sam Houston undercut him? And that Texas only became part of the United States in 1845? Yes, Texas has a LONG and GLORIOUS tradition of independence, and this is just the latest chapter in the story of the U.S. trying to absorb it."

(They don't mention that Texas's admission to the Union was delayed because it was a slave state, but no matter. That's a historical quibble, not worthy of mention. The point is, TEXAS HAS A LONG HISTORY OF INDEPENDENCE).

Preparations to admit Texas to the PSA continue unabated. The Chinese-led world order turns a deaf ear to the American president's demands. "We don't negotiate with terrorists," the world press proudly declares. "We will not heed the demands of the sinister tyrant in his spiderweb in Washington, who's been hacking us for years and trying to undermine the stable and peaceful world order established by the champion of peace and prosperity, Beijing. No negotiation. Accede to Texas's actions. Or else."

In such a situation, I ask you in all seriousness and sincerity: what should the American president do?

Monday, October 21, 2019

Sherlock Holmes and the Jewish Imagination

And we were both crazy about Sherlock Holmes.

Why Max, I, and countless other Jews, are such passionate Sherlock Holmes fans is an interesting question. Jews are rarely mentioned in the Holmes canon, and when they are, it’s not flattering. One “seedy” client is described as “looking like a Jew pedlar;” another has gotten himself into debt and is “in the hands of the Jews;” and one has "a touch of the sheeny about his nose." There’s a smattering of characters with Jewish-sounding names: Irene Adler; a client of Holmes named “old Abrahams” in The Hound of the Baskervilles; and a tailor named Hyams in “The Norwood Builder.” Beyond that, though, the Holmes canon is judenrein.

And Holmes himself—created by the Irish-English Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, based on the Scots Presbyterian physician Dr. Joseph Bell and as recognizably English a landmark in the literary world as Big Ben is in the physical one-- is as goyishe as an Easter ham. Nonetheless, Sherlock Holmes, much like Entenmann’s coffee cake and Dr. Brown’s Cream Soda, is so beloved of the Chosen that he’s become part of Jewish culture.

This phenomenon – the adoption of a creation of one culture by another – is a pretty frequent occurrence, and it goes both ways. Andre Maurois wrote beautifully how Benjamin Disraeli, the grandson of an Italian-Jewish immigrant, became an English institution:

And he did so almost from the moment he first appeared. The Holmes stories were translated into Yiddish soon after their publication in England and were an instant hit. Eastern European Jews (including the young Isaac Bashevis Singer, who once said that it was The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes that inspired him to become a writer) became ardent Holmes devotees. And when they left Eastern Europe for America and other points west, they brought their enthusiasm for Sherlock Holmes with them. In 1947, a Russian-born New York bookseller named Ben Abramson became the editor of The Baker Street Journal, the official publication of the Baker Street Irregulars, the oldest and largest of the Sherlock Holmes fan societies.

Sherlock Holmes has proven his staying power among the Chosen. Even today, over half the BSI’s Board of Directors is Jewish. Reading the Holmes canon from start to finish has been as much a rite of passage as a bar mitzvah for countless Jewish kids.

The trend continues to the present. Many, if not most, of the best known and most notable Holmes pastiches were written by Jews: Nicholas Meyer’s The Seven Percent Solution, The Canary Trainer, and The West End Horror; and Pulitzer prizewinner Michael Chabon’s The Final Solution; Anthony Horowitz’s House of Silk and Moriarty (which books were officially commissioned by the estate of Conan Doyle) stand out.

Jewish reimaginings of Sherlock Holmes didn't stop with books. On screen, Billy Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond - both Eastern European-born Jewish immigrants - wrote the screenplay for, and directed, one of the most acclaimed Holmes movies of all time (1970's The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes). And on television, the best known and most successful Holmes pastiche of all, Doctor Who, was created by Jewish producer Verity Lambert and Sydney Newman, the Canadian-Jewish TV Head of Drama for the BBC who, writes Jill Lepore in the New Yorker, specifically instructed his writers to give the Doctor “something of the feeling of Sherlock Holmes.”

They succeeded. “Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Who,” observes Lepore, “are the same character: the Edwardian amateur. Their stories follow the same formula.”

And there is, finally, my favorite Jewish reimagining of Sherlock Holmes: Joann Sfar’s Professeur Bell graphic novels. Sfar, the French-Jewish comics genius best known to American audiences as the author of The Rabbi’s Cat, has created one of the cleverest and most original Holmes riffs yet with this series (which, sadly, remains untranslated into English - an oversight which which I hope, for the sake of Anglophone Holmes fans, is soon corrected). In this series, Sfar turns Professor Joseph Bell himself, Conan Doyle’s professor at the University of Edinburgh and the inspiration for Sherlock Holmes, into a character.

It’s a neat trick that allows Sfar to have great fun playing with the analogs. Watson has been split into two characters: Eliphas, his smart and useful side, and Ossour, his bumbling and comedic side. Lestrade’s role is played by the hulking Inspector Mazock, and in a twist that makes hard-core Holmes fans gasp by its sheer brilliance and audacity, Bell’s archnemesis, Adam Worth, is the real-life German-Jewish criminal mastermind who was Conan Doyle’s inspiration for Professor James Moriarty.

|

| Joann Sfar's Professeur Bell, a rationalist in a world of ghosts. |

But Sfar mischievously turns Conan Doyle’s steely-eyed rationalism on its head. Sfar’s Bell moves in a magical world, a gothic phantasmagoria of devils and demons, ghosts and revenants, and Bell himself is as much a sorcerer as he is a scientist. While Holmes says, “This agency stands flat-footed upon the ground, and there it must remain. The world is big enough for us. No ghosts need apply,” Bell’s primary assistant, Eliphas, is himself a ghost.

Why Jews should be so prominent among Holmes pastiche-artists may have something to do with the phenomenon of fandom itself, which, arguably, Sherlock Holmes inspired. Rabbi Rachel Barenblat writes perceptively that there is something very Jewish about the culture and act of fandom: “Just as Jews create community through engaging around our shared stories, so do fans. But instead of writing stories or essays or making short films which offer exegeses of Biblical or Talmudic texts, fans write stories and essays… which explore pop culture texts. We respond and re-purpose, turning and turning all kinds of stories to see what might be found inside.”

But Holmes is not the only character about whom countless pastiches have been written, nor is he the only character from that era who remains popular. What accounts for the particular appeal of Sherlock Holmes to the Jewish imagination? Why not Allen Quatermain, Tarzan, John Carter of Mars, or countless other great characters? Why should the subject of that Talmudic dynamic of response and repurposing be Sherlock Holmes?

The enduring popularity of Sherlock Holmes with both Jews and non-Jews has, in my judgment, zero to do with mysteries or crime fiction. Neither genre interests me and never has. My first exposure to whodunits was Donald J. Sobol’s Encyclopedia Brown stories (arguably another example of a pastiche of Sherlock Holmes by a Jewish author), and I didn’t like them. Sobol hid clues in the text that the careful reader would notice and then use to solve the mystery. I very rarely figured them out, and that made me feel stupid.

Coming on the heels of Encyclopedia Brown, the first Sherlock Holmes story I ever read (a Big/Little Books edition of The Hound of the Baskervilles) confused me. Even a naar like me could see that Conan Doyle had given the reader no way to solve the mystery, had hidden no Sobolian clues in the text. It finally dawned on me that Conan Doyle didn’t want readers to solve the Holmes stories. We were supposed to read them. Conan Doyle didn’t give us brainteasers or word problems. He gave us stories—stories about, arguably, the most compelling character in literature. And that, in my view, is the secret of the Holmes stories’ lasting appeal: Sherlock Holmes himself.

I’m going to open myself to the charge of heresy when I say that the Sherlock Holmes stories aren’t really “mysteries,” in the genre sense, at all. Many of them - starting with the very first, A Study in Scarlet - are vehicles for Conan Doyle's real love, which was adventure stories - tales of cowboys, brigands, sailors at sea, mutinies, battles in the Khyber Pass, shoot-outs and gunfights, secret societies like the Klan and Mafia, vendettas and vengeance. Think of "The Adventure of the Gloria Scott," "The Boscombe Valley Mystery," "The Red Circle," The Valley of Fear, etc. They read more like stuff out of Boys' Own Magazine than they do like Agatha Christie or Dorothy Sayers. And the crimes Holmes solves are, in many cases, incidental. They're merely the means by which Conan Doyle showcases the attributes and characteristics of his great character.

I assert this with confidence, because Joseph Bell himself, the inspiration for Holmes, was neither cop nor detective. He was a physician and a professor. And the mysteries he solved weren’t crimes, they were diseases.

It wasn't crime that Conan Doyle was showcasing, it was Bell himself and the processes of his mind—the diagnostic strategy of observation and deduction that Holmes enthusiasts even today refer to as “The Method” – that fascinated Conan Doyle, not “the petty puzzles of the police court,” as Sherlock’s brother Mycroft called his cases. And in fact, Sherlock Holmes himself says as much, when he tells Watson in “The Copper Beeches,” “Crime is common. Logic is rare. Therefore it is upon the logic rather than upon the crime that you should dwell.”

If it's the character and characteristics of Holmes, then, that attracts us, what are those characteristics, and what is the secret of their appeal to Jewish readers?

The obvious and immediate answer is his intelligence. Holmes is brainy, and that in itself appeals to the Jewish reader. The archetypal hero or exemplar in Jewish culture isn’t the fighter, it's the thinker - the guy who uses his brains, not his fists. It isn’t brawny Esau who wins Isaac's paternal blessing, it’s clever Jacob. David the warrior may have built the empire, but it’s Solomon the Wise who is allowed to build the Temple.

And it isn’t just that Holmes is smart—his mental processes have a recognizably Jewish, almost a Talmudic, flavor.

The American humorist Leo Rosten, in The Joys of Yiddish, tells a version of the hoary Jewish joke about the old man on the train who sizes up the young man sitting across from him. By a long internal process of observing and deducing, he figures out that the young man is on his way to propose, and opens a conversation with the young man by blurting, “Mazel tov on your engagement to Miss Sylvia Rosenberg!” Dumbfounded, the young man asks the older one how he could possibly have known that, whereupon the old man smiles and answers, “My dear boy, it’s obvious!” Substitute “elementary” for “obvious,” and it could just as easily have been Holmes himself sitting on the train.

Holmes also resonates with Jewish readers, I suspect, because he’s eerily similar to a type that frequently recurs in Jewish folklore and literature: the Litvak.

Strictly translated, “Litvak”, in Yiddish, means “a Jew from Lithuania." But it implies far more than that. The Litvak had a certain reputation, as the YIVO Encyclopedia describes him:

This sounds an awful lot like Watson’s description of Holmes from “The Greek Interpreter”:

…and like that in “A Scandal in Bohemia:”

This Litvish type—the cold, hyper-rational creature of pure intellect—appears throughout Jewish literature. Perhaps the best known instance of the type is Danny Saunders, the subject of Chaim Potok’s The Chosen. Danny Saunders possesses this kind of cold, hard, merciless, crystalline intellect, and his father the Rebbe, who recognizes the type (his brother, Danny’s uncle, had been one of these brains without a heart), resorts to a drastic solution: he raises Danny in complete silence, devoid of any paternal warmth or love, to break his heart, teach him grief and suffering, and in doing so, teach him empathy, and what it means to be human - to give him a conscience.

Neil Gaiman, in his magisterial Sandman graphic novels, wrote about a dream-library of books never written, but which should have been. One of these volumes is The Conscience of Sherlock Holmes, which, as Gaiman says in an interview in The Sandman Companion, “is the one thing that Holmes didn’t have.” Which makes one wonder what would have happened had Holmes’ father raised him in silence as well.

But and in my more fanciful moments, it strikes me that Noam Chomsky, one of the most brilliant and indignant intellects of our time—he almost single-handedly created the entire discipline of cognitive science, and has been a fierce and uncompromising moral voice in politics --is precisely what Sherlock Holmes would have been, had he possessed a conscience. Chomsky, at least in his younger years, even resembled Conan Doyle’s description of Holmes from A Study in Scarlet:

|

| The young Noam Chomsky--Holmes to the pipe. |

Intellectual similarities aside, there are other elements of Holmes’ character that resonate powerfully with the Jewish reader.

Perhaps foremost among these is the fact that Holmes is an outsider, a status which echoed the position of the stateless and marginalized Jews of Europe. He’s not a policeman or a member of any official or government force, and is, at times, openly antagonistic toward the official police. He doesn’t wear a uniform. He’s an amateur, an independent agent. European Jews, who lived on the margins of European life and who, throughout most of their history, had been prohibited from serving in armies or militias, may well have recognized in Holmes a fellow traveler. And it is perhaps worth remembering that when Sherlock Holmes was appearing in the Strand magazine, the Dreyfus case was raging in France, reminding the Jews of 19th-century Europe what would happen to them if they dared don a uniform or join any official State force.

Not only did he not belong to any instrument of official authority, he was openly contemptuous of it. Holmes answered to a higher morality than the official, state-sanctioned one: his own. Throughout the stories—in “The Blue Carbuncle,” “The Boscombe Valley Mystery,” “The Adventure of the Devil’s Foot,” “Black Peter,” etc.—Holmes decides not to turn the “criminal” over to the state’s authority when he judges that justice would be better served by not doing so. He acts according to his own lights—another characteristic that parallels the Jewish experience. Jews, throughout the course of our long history, have frequently been obliged to choose between the law of the state and the law of God. Generally, we've opted for the higher authority.

In another echo of Holmes to Jews, he is the quintessential urbanite—a resident of one of Europe's largest and most cosmopolitan cities (so devoted to the London metropolis that he keeps an exact map of London in his head), an apartment dweller whose regard for rural life borders on revulsion. He detests and distrusts the countryside, as he says to Watson in “The Copper Beeches:”

One of the most thumbed-through volumes on my shelf of Holmesiana is Sherlock Holmes Through Time and Space, a collection of short stories by Isaac Asimov, Poul Anderson, Gene Wolfe, and others that place the Great Detective in a wild variety of settings: America, outer space, other planets, in the far future, etc. He moves effortlessly from era to era and place to place. And he was doing so long before that book’s publication. Basil Rathbone’s Holmes easily made the transition from fighting Moriarty to fighting the Nazis; and in more recent time, Benedict Cumberbatch’s incarnation is as at home using a smartphone as the original was using a magnifying glass.

Like the Jews, Sherlock Holmes originated in a time and place that no longer exists. His very name evokes Victorian London’s gaslit, fog-choked streets and his cozy digs in Baker Street as much as the Jewish sacred texts evoke a desert society of 3,000 years ago. But he is no more dependent upon his original context than is Judaism. Both Sherlock Holmes and Judaism are flexible tropes, adaptable enough to thrive in almost every human context, durable enough to survive the Diaspora and the Great Hiatus. They are both ageless yet contemporary, open to revision, reinterpretation, and reimagining by every generation.

Sunday, July 20, 2014

Highway Zekhtsik-Eyn Revisited: Paul Kriwaczek's "Yiddish Civilization."

It's the sort of mind that another late hero of mine, the shamefully unappreciated speculative fiction writer Avram Davidson, had. Shortly before he died, he produced a strange and rather marvelous book--Adventures in Unhistory--wherein he sifts through the accumulated data of a lifetime of reading and divines connections between them to trace the origins of legendary beasts like dragons, phoenixes, mermaids, the Rough Beast Slouching Towards Jerusalem, werewolves, etc--to their decidedly unlegendary and mundane origins. And so did my idol, the legendary Joseph Pulitzer, who was famous--in some quarters, feared--for his truly prodigious memory, for his eerie ability to recall from it the smallest, most niggling, and most arcane of data, and for his ability to draw connections between, and see patterns in, the seemingly unrelated bits of data residing in the massive storehouse of his powerful brain.

It's the kind of mind one might flippantly describe as "Talmudic," although, since Davidson, Pulitzer, and Kriwaczek were all Jewish, perhaps not as flippant as it might seem at first. Because their mental processes and methods--cramming the mind full of data and then training it to make connections between seemingly disparate and unconnected bits of information--are, in fact, precisely those utilized by generations of Talmud scholars of Central and Eastern Europe.

Which brings me back neatly to Paul Kriwaczek.

He died too soon, having written only three books. I wish he'd been able to write more. But the three that we do have--In Search of Zarathustra: The First Prophet and the Ideas that Changed the Word, Babylon, Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilizations, and Yiddish Civilization: The Rise and Fall of a Forgotten Civilization--are magnificent. They are all about the fluidity of human civilizations, about how of ideas move from people to people, and the resulting transmutations of those civilizations themselves--how they shape, and are shaped by, the ideas which they transmit and to which they give rise, and all about the strange things that happen at those borders. These are the kinds of things I'm interested in. Yiddish Civilization--his second book, and the one he was most proud of--powerfully engaged me, perhaps because he says something I've been thinking about for a long time, and in doing so challenges something that's bothered me ever since I started thinking about it.

I watched the film Schindler's List with a granddaughter of victims of the Babi Yar massacre, which magnified the emotional effect of the movie a thousandfold. We were not romantically involved, but our hands sought out each others', and long after the movie was over, we continued to cling to each other.

But when I saw it a second time with my mother, the experience had much less of an impact. It didn't move me, it irritated me, and I wasn't sure why. But I realized what was bothering me later, as I watched Hollywood roll out a parade of other Holocaust-themed movies--Jakob the Liar, The Pianist, Life is Beautiful, etc.--in Schindler's wake.

The much maligned historian Norman Finkelstein, himself the child of Holocaust survivors, maintains that the Holocaust has been cynically suborned to drum up support and sympathy for what is essentially an apartheid state. While I don't agree completely with Finkelstein's analysis, I too am bothered by the emphasis placed on the Holocaust for two reasons.

First, it implies that Jewish suffering is unique, which is untrue. The Roma were also nearly wiped out by Nazis, and given enough time, the Slavs wouldn't have fared much better--the Nazis planned to murder half and use the other half as slave labor. And moving beyond the Holocaust, the Armenians, the Anatolian Greeks, the Kurds, the Tutsis, and many other peoples have suffered attempted genocide.

Secondly, this unrelenting emphasis on the Holocaust reduces three thousand years of a people's history to the six worst. If you ask any non-Jewish American one thing he or she can tell you about the Jewish people, chances are very few of them will be able to tell you about the aforementioned Joseph Pulitzer. Or Albert Einstein, or Sigmund Freud, or Benjamin Disraeli, or Jonas Salk, or Karl Marx or Moses Mendelssohn, or Ludwig Wittgenstein, or Franz Kafka, or David Ricardo or Judah Cresques, or Benedict Spinoza, who more or less singlehandedly ushered in the age of modernity, or Moses Maimonides. Or Jesus and Saint Paul, or Moses. Or any of the other Jewish luminaries whose ideas helped shape the world. But they WILL be able to tell you that the Jews are awfully good at getting killed.

Viewing Jewish history from our post-Holocaust vantage point only strengthens what Salo W. Baron, the great Columbia Jewish historian, called the "lachrymose interpretation": the tendency to read Jewish history as an unbroken chronicle of suffering, one long stretch of pogrom after expulsion, a long and miserable slog through the Valley of the Shadow of Death beginning with the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE.

It's a depressing and, to be honest, rather self-indulgent view of Jewish history, leading, as it does, to the conclusion that the Jews survived as a people due to some inherent superiority of the culture or traditions, which is nonsense--Jewish exceptionalism is as pernicious and dangerous as is any other kind--or because of divine protection, which is also nonsense.

Kriwaczek opens his book by noting the amnesia among the Jews of his generation in regard to the most recent chapter of their past, which was Eastern Europe. If that first generation of immigrant Jewish children, and their children, identified with any aspect of Jewish history of all, it was with the Biblical rather than the more recent, a tendency perhaps strengthened by the re-establishment of a Jewish state in the land of the Bible itself, in 1948. Many of them had (or feigned having) no idea of, and no interest in, where in Europe their parents or grandparents had come from. It's a phenomenon I observed firsthand--only grudgingly did my grandmother reveal that she knew where her father, my great-grandfather, was born (in the Polish city of Plock). She was an American. The Old Country was irrelevant and an embarrassment. It was almost like incest or alcoholism--a dark and tragic episode of family history that we'd all be much better off forgetting, thank you very much, so let's not speak of it again.

Yiddish Civilization, I hope, will serve as at least a partial correction to that attitude, because it challenges this paradigm and paints a radically divergent picture of Jewish history.

Kriwaczek's opening contention that today's Jews are the descendants not only of Judaean exiles, but are a duke's mixture of many different peoples, isn't a new one. It's ground already well-trodden by many, including the Marxist historian Abram Leon (who wrote that "the most superficial examination of the question leads us to the conclusion that the Jews constitute in reality a mixture of the most diverse races. It is evidently the Diaspora character of Judaism which is the fundamental cause of this fact. But even in Palestine, the Jews were far from constituting a 'pure race'”) and Arthur Koestler, who, in his mischievous Thirteenth Tribe, suggested that the bulk of Ashkenazic Jewry descended not from exiled Judaeans but from a Turkic people, the Khazars, at least some of whom converted to Judaism somewhere around the 7th century.

Kriwaczek is more measured and humane than any of these, and his contentions less calculated to inflame. Certainly the Jewish people, even before the destruction of the Second Temple, was already both widely dispersed, with large communities in Babylon, Persia, Greece, Egypt, and even Rome itself, and highly heterogeneous, having already absorbed a fair amount of their neighbors, like the Aramaeans and the Idumaeans (the Edomites of the Bible). Moreover, they were at that time pretty active proselytizers as well. Many early Diaspora communities were comprised largely--in some cases, entirely--of local proselytes. And it is at this point, against the backdrop of the early Diaspora, that the Yiddish civilization and people begin.

Ethnogenesis--the beginning of a people--is a messy and imprecise process. Every national or ethnic group is, undoubtedly, made up of a bunch of different peoples who, over the course of time, a few shared experiences, and the gradual adoption of a genesis myth and a single language, begin to think of themselves as one people. The Ashkenazic Jews of Central and Eastern Europe were no different. Kriwaczek identifies two ancestral strains--the Latin-speaking Jews of the Roman Empire's west, and the Jews of the Empire's east, Greek by language, culture, and in many cases, ancestry--which moved across Europe in two different directions. Along the way, the Latin Jews moved north and east into the Germanic regions, abandoning Latin for German as they did so; the Jews of the Greek sphere moved north and west into the areas around the Black Sea, picking up Greek, Slavic, and Turkish converts on the route as well, abandoning Greek for Slavic as the Latin Jews ditched Latin for German, and settled across Slavic Eastern Europe.

Eventually, the two strains met in the middle--at Ratisbon, as the city was called by its original Celtic inhabitants, renamed Regensburg by the Germans who eventually came to possess it--and hammered out a shared language: Yiddish, that weird and wonderful hybrid of German, Slavic, and Hebrew. It is in Regensburg, he says, where the two strains: the western-Latin-German Jews and the eastern-Greek-Slavic Jews--came together in what became known as the Heym, or "homeland": the great Jewish nation within the Catholic Slavic heartland of Europe.

The fusion was a little imperfect. The German Jews looked down on their Eastern co-religionists, who were rather unlearned and whose "Judaism" was idiosyncratic at best, and certainly not according to Hoyle. This faultline persisted right down to the present day. But even if there was a little snobbery on the Germans' part, the two strains melded, creating one of the great nations of Europe--a nation not of eternal wanderers and aliens, guests in someone else's country, but just as "indigenous", and in some cases more so, as any of their neighbors.

Thinking of Yiddish Jewry (as differentiated from the Ladino-speaking Sephardim of the Mediterranean, or the Arabic-speaking Mizrachim of the Middle East) within the context of broader European history--as an emerging European nation alongside many other emerging European nations--gives us the opportunity to consider Jewish history comparatively instead of in a vacuum. And from that perspective, Jewish history doesn't look quite so bad.

Jews, along with many other peoples, poured into Eastern Europe in the medieval period the way American pioneers moved west, and for the same reason. Thinly-populated Eastern Europe, much like the American West, was the land of opportunity. And the Yiddish Jews of the Heym made out pretty well in Poland, Lithuania, and elsewhere throughout Eastern Europe. They enjoyed a remarkable amount of autonomy, regulated their own affairs through their own national government--the Council of the Four Lands--and on the local level through the Kehillot, the local self-governing units of individual Jewish communities. They outnumbered Christians in many places, and generally did better economically, enjoying favored status and exclusive control over certain economic functions, like tax-farming. granted by kings and noblemen who valued their expertise. They weren't merely a part of the emerging Eastern European economy, they WERE the emerging Eastern European economy, advantaged as they were by a long mercantile tradition and connected culturally and economically with other Jewish communities across the world.

Was there suffering? Undoubtedly. But those were brutal times, and everyone suffered, some peoples far worse. Nor, says Kriwaczek, were Jews generally singled out for persecution. The Inquisition, for example, didn't target Jews specifically. It went after everyone who deviated from orthodox Catholicism, including Muslims, Cathars and Bogomils (whose history as secret Zoroastrians he traces most enjoyably in his Zarathustra book), Albigensians, and everyone else. Jews may have been expelled from time to time and in certain places, but they weren't alone. Lots of people were expelled from lots of places, and in most cases, the Jews were let back in pretty quickly. The Crusaders may have gone after them, but they also went after Albigensians, Eastern Orthodox Christians, and, on occasion, each other. And being Jewish may actually have spared the Jews a good deal of suffering as well. As non-combatants in the Catholic-Protestant wars, they missed the worst of Christian internecine fighting, and even made out pretty well, numbers-wise--whole communities of Czech Protestants, when the fighting went against them, converted en masse to Judaism instead of returning to the Catholic fold, and were absorbed part and parcel into the Heym.

Kriwaczek is too much of a gentleman to say it aloud--his books refrain from attacking other historians--but there runs throughout Yiddish Civilization a sort of good-natured implied rebuke to those historians who concentrate on the Jews exclusively, throwing context out the window; and who extrapolate the worst events to befall them as emblematic of their entire history. In contrast to the picture presented by the "lachrymose interpretation," Kriwaczek reimagines the Heym as a large, vibrant, and in many ways quite powerful member of the European family of nations.

When things did go south in Eastern Europe, the Heym too suffered. Eastern Europe's economic collapse in the 17th century hit the Heym hard, as did the Khmelnitsky massacres in Ukraine (although, as Kriwaczek is quick to point out, the Cossacks who murdered Jews killed a lot more Poles, and generally did it far more brutally). The Heym's long, slow decline mirrored that of Eastern Europe's, culminating with the Third and final partition of Poland in 1795, which brought much of the Heym under Russian domination (although, as Kriwaczek also points out, the end of Poland was disastrous for the Poles as well). The Russians penned the Jews into the Pale of Settlement, severely circumscribing their movement, barred them from certain professions and from land ownership, and abolished the Kehillot (the Council of the Four Lands had been done away with earlier), ending their self-governing communal autonomy and hastening the Heym's demise. Under the Russian Tsars, the Yiddish Jews of the Heym became how they are viewed today: a despised, marginalized, downtrodden, and alien minority existing at the fringes of society, suffered only grudgingly, if at all, by the Christian masters of Europe.

It got worse after the assassination of Alexander II in 1881 (the assassins included within their number one Hessie Helfman, a Jewish girl), the ascension of the reactionary Alexander III, whose Procurator of the Holy Synod, Konstantin Pobedenostsev, enacted policy designed to bring about what he thought would solve Russia's Jewish problem: one-third of the Jews should be killed, one-third forced to emigrate, and one-third totally assimilated into Russian society. Pogroms broke out, instigated, as Michael Aronson argues in his book Troubled Waters, by the Tsarist government.

In response to the latest wave of Tsarist persecution, much of the Heym, already reeling, simply uprooted itself. Millions of Yiddish Jews just picked up and left, going either West to Europe and America or south to Palestine. And the disasters of the 20th century simply finished the job. World War I, the Russian Revolution, and, finally, the Holocaust, conclusively killed off what was left of the Heym.

The great Jewish nation of the Heym is now one with plenty of other communities, Jewish and non-Jewish, which have moved elsewhere, merged with other communities, or ceased to exist altogether. But even if it no longer exists except as a fading (and often suppressed) memory, the Heym was the crucible of the modern Jewish people. It's where the vast majority of today's Jews originated, forming modern Jewry's attitudes and informing its identity. It is as as crucial a chapter in Jewish history as was the Babylonian, Greek, or Spanish chapters, and will, G-d willing, someday be remembered that way.

Friday, July 11, 2014

Deconstructing Ann Coulter

|

| Ann Coulter today, the snarling darling of the Far Right fringe. |

|

| Ann then, as a high school student at New Canaan High School. |

At Cornell, she quickly discovered that some men like tall, blonde, blue-eyed, willowy women, and she, to quote Naomi Wolf, bloomed in the sunlight that is male sexual attention. Or to put it more concisely and less poetically, she slutted out. Once she realized she was desirable, she gave it away like candy at Halloween. She threw it out there like nobody’s business. She took all comers. She not only became easy, she became notoriously so.

She’s probably beyond redemption, but, properly interpreted, she serves as a terrific object lesson. If we want to keep others like her from spawning and germinating, all we must needs do tune her out, ignore her screeching prescriptions, and extend respect, compassion, and empathy in all arenas, personal and political, to those who need it.